Introduction

In 2008, as the Olympic flame flickered in Beijing, it seemed China’s time had come. After the ‘century of humiliation’, in which outside powers had subjugated the country, China appeared to rise as a global economic and military power. Gaining confidence, China jettisoned Deng Xiaoping’s strategy of ‘keeping a low profile’ (Xuetong, 2014, p.156) and adopted a more assertive foreign policy; isolating Taiwan, strengthening its peacekeeping credentials, militarising the South China Sea, and leading the Global South. With the election of US President Donald Trump, China’s global leadership seemed cemented. Xi Jinping defended globalisation while ensuring China remained a signatory to the Paris Climate Accord and the Iran Nuclear Deal. Although the pandemic damaged China’s reputation, its global ambition remained strong, and in December 2022, it led to a historic UN global agreement for biodiversity in Montréal. For many, China’s rise exemplifies the geopolitical theories of Paul Kennedy, Martin Wight, and others in proving the relationship between economic strength, national rise, and the pursuit of global ambitions.

However, in light of a faltering economy and changing demographics, a growing chorus of western policymakers, think tanks, and scholars have questioned China’s potential as a world leader, with many concluding that domestic problems could lead to the country’s downfall. After years of China’s inexorable rise dominating discourse, the pendulum has swung towards a more pessimistic narrative. On the economic front, Daniel Rosen talks of “China’s economic reckoning” with China having “at most a few years to act before growth runs out” (Fosen, 2021, p. 20). Michael Pettis suggests China has “trapped itself” with an economic model that “has left it with only bad choices” (Pettis, 2022, para. 1) while Ruchir Sharma in the Financial Times claims, “China is unlikely to overtake the US until 2060, if ever,” (Sharma, 2022, para. 2). China is also seen as facing a “demographic disaster” (Black & Morrison, 2019, para. 6) and engaged in a “doomed fight against demographic decline” (Minzner, 2022, para. 1). Zooming out and looking at the bigger picture, Roger McShane, China Editor for the Economist, asks, “has China reached the peak of its powers?” answering dramatically that “fearing economic strangulation by America, [China] could be more dangerous” (McShane, 2022, para. 6).

Despite the prevailing narrative among western commentators, this essay will argue that China’s domestic problems will not lead to its downfall. The first section will establish the link between ‘power’ and world leadership, providing a theoretical framing for focusing the essay on China’s economic and demographic challenges. The second section will make the case against downfall, arguing that China’s size reduces the threat while the slow nature of demographic change gives China time to adjust through its ongoing reforms. On the economic front, an argument will be made that China’s economic problems have been overstated and that its unfulfilled potential and early signs of success in transitioning to a consumer-led economy point to its continuing rise. Finally, the third section will examine some of the most common counterarguments, including the frequently made comparison between Japan’s ‘lost decade’ and predictions of China’s demise.

Section 1: The Power Formula

Before making the case against downfall, it is crucial to establish the reasons for focusing on, and evaluating China’s demographic and economic challenges. Here, we can use the theories of international relations to help frame and contextualise our focus.

There is a consensus that China’s world leadership stems from its demographic and economic strength. For the purpose of this essay, power can be used as a proxy for ‘world leader’. As Martin Wight suggests, power consists of “size of population, strategic position and geographical extent, and economic resources and industrial production” (Wight, 1978, p.26). Similarly, Ikenberry talks of economic might as a key ingredient for world leadership (Ikenberry, 1996, p.389). Kennedy, in his seminal theory on the ‘The Rise and Fall of Great Powers,’ argues that without a “flourishing economic base,” you cannot be a great power (Kennedy, 1989, p.697) while also suggesting that “both wealth and power are always relative” (Kennedy, 1989, p.25). Furthermore, Kennedy posits that the US and Britain’s historical experiences exemplify the link between economic power and global leadership. He connects Britain’s global leadership to its economic position, whereby in 1860, Britain was “responsible for one-fifth of the world’s commerce, but for two-fifths of the trade in manufactured goods” (Kennedy, 1989, p.194). Given that China today represents 15 percent of global trade (UNCTAD, 2021) and 28 percent of global manufacturing (Worldpopulationreview), it is reasonable to suggest a causal link between economic strength and global power.

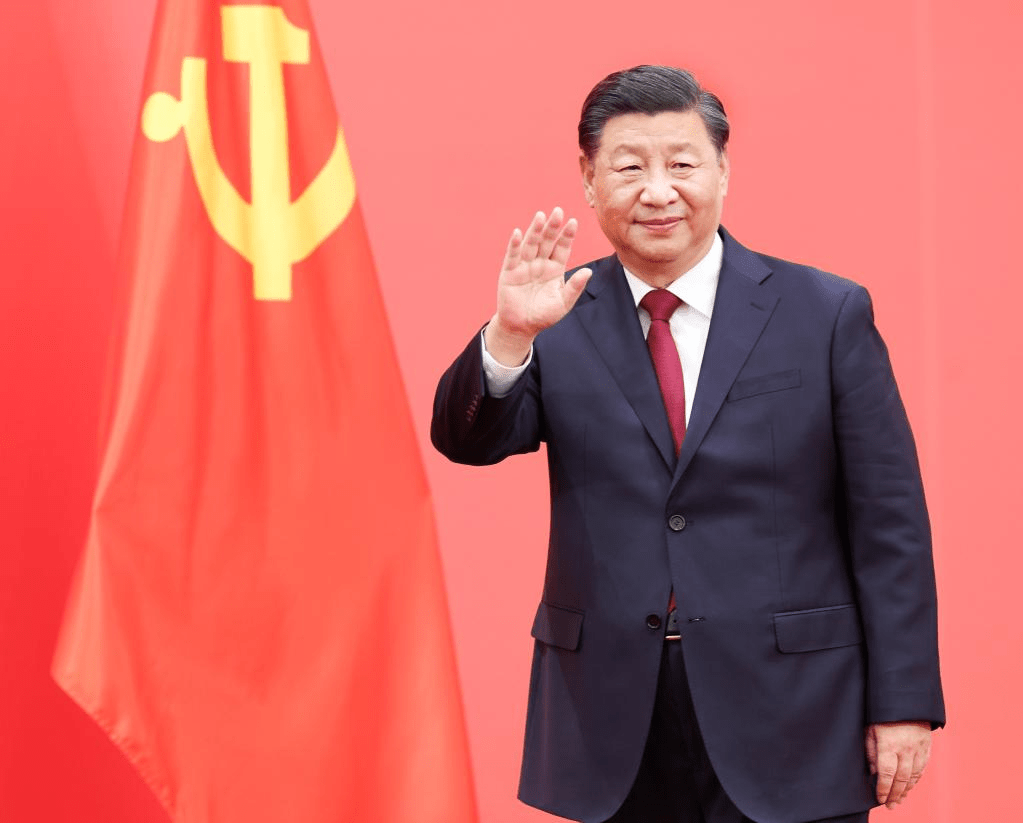

In the context of modern China, as the economy has expanded, it has made significant strategic investments to enhance its global power. Investing over $1 trillion in its Belt and Road Initiative, China is building ports, bridges, and railways across 80 countries to improve trade connectivity, market access, and by default, geopolitical power (Hillman, 2018). China’s investment in global infrastructure exemplifies Kennedy’s position that states strive to enhance their wealth and power to “become (or to remain) rich and strong” (Kennedy, 1989, p.15). China’s global ambitions require significant investment. As Williamson Murray argues, a grand strategy requires the means to connect to the ends (Murray, 2011). In other words, a country needs the resources necessary to accomplish its objectives and, by default, requires a healthy economy. The importance, therefore, of domestic strength is critical in ensuring China can act on the world stage. As the former Australian Prime Minister and China specialist Kevin Rudd point out in his book ‘Avoidable War,’ “strength at home is fundamental to whatever ambitions Xi may pursue abroad” (Rudd, 2022, p.179). Xi himself underscores this point. He spoke at the Communist Party’s 20th Congress of his desire to avoid the “historical cycles of order and disorder, rise and fall” (Osnos, 2022, New Yorker, para.3), whereby China’s previous rules failed to prevent China’s eventual demise through a mix of international and domestic problems (Osnos, 2022).

Following the theories of Kennedy, Wight, and Rudd, it would appear that any economic or other domestic malaise could jeopardise China’s potential as a world leader or, at the very least, require its re-calibration. Taking Kennedy’s theory to its conclusion, a failure in economic power could lead to the fall of great power, in this case, China.

Section 2: Domestic problems will not lead to downfall

The demographic downfall argument doesn’t add-up

With the birth rate falling to 1.3 births per woman compared to the required replacement level of 2.1 (Minzner, 2022), China’s population will shrink from 1.4 billion (World Bank, 2022) today to 1.3 billion in 2050 and 700 million by the end of the century (Xin, 2022). In parallel, China will also get older, with over 65s representing a quarter of the population by 2050 (Rajah & Leng, 2022). As a result of these changes, China will lose up to 200 million workers (Black & Morrison, 2018), putting an end to its demographic dividend that drove its transformation, while its increasingly ageing population will add a significant economic burden in terms of welfare.

However, the argument that demographic decline will lead to China’s downfall ignores the reality of China’s size, the slow pace of change, and China’s ability to offset demographic headwinds through reform.

While China’s population will decline, it will do so slowly and will not experience a “cliff-like fall” (Xin, 2022). For the rest of this century, the country will remain far larger in terms of population than the United States or the European Union. As Gideon Rachman in the Financial Times points out, China’s sheer size means it does not need to reach parity with the US on per-capita terms to overtake it as the world’s largest economy. Moreover, while India’s population will surpass China in 2024 (Our World in Data), it remains unlikely to challenge China economically, given that its economy is only 20 percent the size of China’s (Rachman, 2022). Therefore, it is safe to assume that in 2050 China will remain the world’s second most populous country with the potential to overtake the US economy with the continued ability to project its global power.

Even arguments that a shrinking workforce will damage China to the point of downfall overstate the link between population and economic power. As Mastro and Scissors suggest China’s economy has continued to grow and has outperformed US economic growth despite the likelihood that its workforce has been shrinking for several years (Mastro & Scissors, 2022). This would suggest that given China’s ability to grow its economy irrespective of workforce shrinkage, the forecasts of demographic impact should be treated more cautiously.

Furthermore, even if, over time, a shrinking population was proven to harm China’s economy, the country has levers it can pull to offset the impact of decline. With only 29 percent of those aged 60 active in the workforce, and with women over 50, in particular, likely to be economically inactive, China has a significant opportunity to increase its workforce through reforms to the retirement age, improvements to education, and a transition to a consumer-led economy with less onerous jobs better suited to older workers (Kroeber, 2020). As some models show, if China increased its older working population to a similar level to Japan’s, it would increase its workforce by 40 million (Hofman, 2021), allowing China to offset any economic impact of a shrinking workforce.

With the pace and the true impact of demographic change remaining unpredictable (Mastro & Scissors, 2022), China has time to adjust and develop its evolving welfare state. As George Magnus points out, China still has the time and ability to tackle the issues that come with demographic change, including focusing on workforce expansion, productivity, and welfare (Magnus, 2018). As early as 2000, the government focused on pensions with reforms in rural areas in 2009 and urban areas in 2011, which as a result, meant that over 125 million people could access a pension by 2012 (Luo, 2015). The progress continues, with China in 2019 inviting foreign companies including Prudential and Generali, to help develop China’s pension provision (John & Chatterjee, 2019). More recently, China also launched a private pension program in 2022 across dozens of major cities, including Shanghai and Chengdu, further strengthening its emerging welfare state (Reuters, 2022). While China will face growing pension costs estimated to rise from 4 percent to 20 percent of GDP by the end of the century (Peng, 2022), this is similar to the OECD average in 2020 (OECD, 2021). It is also important to note that China is not alone in facing an ageing population, with Japan, the US, and much of Europe in a similar situation. While there is no denying the challenge posed by an ageing population, China has begun concerted efforts to alleviate and mitigate the worst possible impacts.

Aside from reforming welfare and increasing the workforce, China can also tackle demographic changes in ways unthinkable in other countries. As Minzner suggests, following its experience with anti-natalist practices during the one-child policy era, China could return to more state-led social interference, such as integrating population growth targets into local government planning. Furthermore, Minzner points out that China has already communicated intentions to limit non-medical abortions and could implement further restrictions on women’s reproductive rights. (Minzner, 2022). While unpalatable to many in the west, China has shown a remarkable ability to direct its population and control desired outcomes in the past. It could do so again if it deems demographic change a drag on national and global ambitions.

In focusing on changing demographics, the China downfall school overstate their impact. Despite these changes, in 2050, China will remain the second most populous country on earth, with an economy more significant than India and potentially on track to overtake the US. The slow nature of demographic change allows China to continue implementing significant reforms to offset the impact of changing demographics. It also has the potential levers, no matter how unsavoury, to mitigate any potential impact.

China’s economic rise will continue

Despite worries over debt, an unbalanced economy, and low consumption, China’s strengths outweigh its weaknesses. China’s untapped potential, ambitious economic plans, and emerging signs of success in transitioning to a consumer-led economy point to a continued rise rather than a downfall.

As Pettis argues, China has invested 40 – 50 percent of its GDP annually, pushing debt to 280 percent, with concerns that over-reliance could become unsustainable, leading to a “very disruptive adjustment” (Pettis, 2022, para.15). However, while Pettis is correct in pointing out the scale of the challenge, talk of a financial crisis is overstated. As former World Bank China Director Yukon Huang points out, China is unlikely to “fall off a financial cliff” (Huang, 2018, p. 66) given that China’s debts sit mainly with the state and are not in private hands, as had been the case in other dangerously exposed economies. Furthermore, Huang suggests that while China’s debt will impact growth, it will not lead to a financial crisis due to the state’s ability to intervene and prevent further problems (Huang, 2018). In contrast, despite widespread concern following the Evergrande crisis between 2020 and 2022, China’s failure to intervene did not cause a broader economic shock. As Dudash suggests, there was no Chinese ‘Lehman brothers moment’ (Dudash, 2021), suggesting that debt, while a challenge, is not an early symptom of coming demise and is something China can manage. Similarly, Magnus argues that despite China’s recent stock market turbulence, a Renminbi crisis, and excessive investment, a debt crisis is unlikely and that, instead, the country likely faces reduced economic growth (Magnus, 2018). This points to the fact that China has undergone economic shocks and has been able to adjust and recover. The impact of debt is also overstated, with Mastro and Scissors pointing out that China’s investment in research, technology development and military modernisation does not seem to have been curtailed despite debt representing 263 percent of GDP in 2019 (Mastro & Scissors, 2022).

The argument that China’s economy is unbalanced is fair. However, it fails to contextualise in light of the experience of other rising powers in the region, misses the likelihood that consumption is under-recorded, and fails to focus on progress made towards transitioning to a consumer-led economy. These factors further erode the case for highlighting economic challenges as a sign of downfall.

While it is true that China’s focus on investment has led to lower consumption, this is common with other countries and has historical precedence. As Huang points out, other Asian countries, during their transformation, also invested heavily in infrastructure, especially in light of urbanisation, and they too, experienced a drop in consumption. He argues that China’s experience is simply a repeat of South Korea’s and Taiwan’s, which successfully transformed into consumer-led economies through high levels of investment and temporary low consumption (Huang, 2022). Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that China is still undergoing its economic transformation and that its current imbalance is a temporary symptom rather than a structural defect likely to bring about China’s downfall.

As Kroeber suggests, Chinese consumption is also likely higher than currently recorded. He argues that given the authorities’ preference for focusing on investment, it is likely that large areas of consumption, such as recreation, are not being counted. Furthermore, he suggests that if corrected, consumption could rise as a share of GDP to as much as 40 to 45 percent (Kroeber, 2020). Such an improvement in consumption share would undermine those that point to an unbalanced economy as a sign of coming economic demise. While Pettis and others question China’s success in transitioning to a consumption-led economy, early signs are encouraging, with consumer spending and pay growing faster than the overall economy (Kroeber, 2020). There is also evidence that services and consumption represent a larger share of GDP than construction and manufacturing (Rothman, 2022). Those who posit that China’s economy is unbalanced overstate the problem, isolate China as a unique outlier ignoring historical precedents, fail to critique consumption data, and overlook China’s early success in transitioning to a consumer-led economy.

Taking a broader view of the Chinese economy, it retains enormous potential providing further reasoning to suggest that downfall is unlikely. Even if, by 2050, the population drops to 1.3 billion, the country’s economic base remains significant. China still has over 900 million people who are yet to enjoy the benefits of China’s economic transformation (Rosen, 2021), while the country will create an astonishing 71 million upper and high-income earners in the next three years alone (Zipser et al., 2022). As Jacques suggests, by 2025, 33 percent of Chinese citizens will still live in the countryside, meaning urbanisation still has some way to go, with China taking longer to urbanise than previous Asian economies (Jacques, 2012). If we take China’s lower consumption rate of 39 percent compared to the global average of 63 percent (Ignatius, 2021) and combine it with China’s household savings which represent 44 percent of GDP (White, 2022), the scope for economic growth is significant. As Zhang points out, the IMF has calculated that if Chinese households spent like their Brazilian counterparts, overall consumption would more than double (Zhang et al., 2018). With new consumers joining the ranks of those already powering the service-led economy, China can grow further.

China’s plan to increase internal consumption through its ‘New Development Concept’ announced in 2020 will see China attempt to increase domestic demand within its vast internal market (Dual Circulation) underpinned by homegrown industries, technologies, and products (Self-Reliance) (Rudd, 2022). The opportunity presented by China’s internal market is already well understood. As Wested argued in 2019, during threats of increasing tariffs against China, the country’s internal market would be able to “fuel the country’s economic rise for years to come” (Wested, 2019, para. 11). Moreover, given China’s investment capability and historical experience in transforming into an economic giant, China’s shift to consumption, while challenging, is possible. Given that possibility the chance of downfall is reduced.

Section 3: A Declining China?

The China downfall school represents a broad group of western scholars, commentators, and policymakers, with some more pessimistic than others and many likely to dispute their inclusion as a proponent of the downfall argument. This section will critically review some of the most common counterarguments, particularly the risk of economic-related civil strife, China’s poor reform record and the comparison often made between Japan’s ‘lost decade’ and China’s potential future demise.

In highlighting economic problems, downfall proponents point to the risk of civil strife. Rudyak suggests that the recent Covid protests in Shanghai, mortgage protests in over 100 cities, and bank runs following the Evergrande crisis illustrate the potential for trouble should China’s economy lose momentum (Rudyak, 2022). Similarly, Tepperman argues China will find itself stuck in the middle-income trap with worsening quality of life for its citizens, provoking the danger of civil strife (Tepperman, 2022). While civil strife is a risk, many fail to appreciate the sheer volume of protests that happen daily in China and the government’s ability to control and mitigate the risks. While China has more than 70,000 protests each year (Jacques, 2012), few become nationwide and as recent Covid protests show, China has a pragmatic ability to listen and pivot when it understands the risk of continuing with an unpopular policy.

Moreover, China’s risk of demise is often attributed to its failure to reform. In highlighting efforts to introduce property taxes and reduce local government borrowing, Rosen summarises the attempts as taking “two steps forward, two steps back”, with Chinese leadership reneging on previously successful local approaches to reform (Rosen, 2022, p.23). Similarly, Rudyak points out that China’s move away from local policy development and reform has compounded the chances of failure that risk serious social unrest (Rudyak, 2022).

While criticising China’s reform record is fair, it doesn’t take into account the significant reformist strides the country has taken and the timescales necessary to complete the reforms China requires. Taking healthcare as an example, between 2004 and 2014, China increased healthcare insurance coverage from 200 million to the entire population, which is unprecedented. While Pettis may criticise the lack of progress in moving to a consumer-led economy (Pettis, 2022), it is important to remember the four decades it took China to evolve from an agrarian to a manufacturing economy. Change takes time, and reforms will inevitably involve incrementalism, rollbacks and abrupt changes. They will also sometimes require central control, especially given the country’s complex domestic challenges.

In attempting to predict China’s future, some argue that it will likely repeat the Japanese experience during its long-term recession. Despite many scholars believing Japan was likely to be the number one economic power of the 21st century (Kennedy, 1989), its economy went into freefall, with the average growth rate slowing from 4.6 percent from 1951 to 1991 to 0.7 percent during 1991 and 2003 (World Bank). The explanations for Japan’s economic demise are well documented. In his book “Japan Story,” Christopher Harding argues that decisions to open up the Japanese economy to outside imports combined with increased infrastructure spending, stocks and land speculation, and poor policy responses were to blame (Harding, 2018). Others, such as the World Bank, point to Japan’s falling investment in research and development and the drag on productivity. (World Bank). Other common arguments point to unfavourable demographic changes, including a shrinking and ageing population.

Delving deeper and focusing on demographics, Black and Morrison point out that Japan’s drop in birth rate from 2.1 births per woman in 1965 to 1.6 in 1989 is similar to that experienced by China. They also point out that Japan’s 13.4 percent fall in workforce population between 1997 to 2017 is similar to that projected for China at 20 percent. Moreover, they also predict that China, like Japan, will struggle to maintain growth via improved productivity, pointing out that China’s productivity trajectory is going in the wrong direction, following the same pattern as Japan (Black & Morrison, 2019).

However, while the comparisons with Japan are interesting, they fail to consider the significant differences between the two countries. Firstly, as Kim Iskyan, an expert in Asian financial markets suggests, China is at a different stage of development compared with Japan. He points out that China is still halfway through its transformation, with GDP per capita at only 14 percent that of the US compared to the 80 percent recorded by Japan at the time of its downturn (Iskyan, 2016). This indicates there is still plenty more scope for growth. Secondly, China is likely to benefit from productivity growth given its recent focus on technology research and development, in contrast to Japan, where cuts were made, and productivity gains through technology had been exhausted (Keyu, 2016). Finally, Johnstone argues that China’s younger population is better positioned to drive a consumption-led economy than was ever the case in Japan, where the young felt less wealthy and lacking in opportunities (Johnston, 2019). While data patterns suggest China will follow Japan, closer inspection uncovers fundamental differences that undermine the proposition. Aside from differences in timing and demographic impacts, China’s sheer size needs to be carefully considered. It is, after all, a vast country with a huge population still undergoing development which differs considerably from Japan. Despite the counterarguments likely to be put forward by proponents of downfall, this essay contends that the case against downfall remains far more convincing.

Conclusion

Despite economic and demographic challenges, there will be no Chinese downfall. China’s domestic problems are significant but not insurmountable. China, in 2050 will remain the world’s second most populous country ahead of the US and the European Union. While India will have overtaken China in population, China will remain the world’s second-largest economy and may, by mid-century, be in a position to overtake the US. China’s continued strength and growth opportunity hold the key to the “flourishing economic base” that Kennedy (Kennedy, 1989, p. 697) suggests is necessary for great power status.

China’s demographic changes will emerge slowly, giving China time to adjust and implement reforms to retirement, pensions, and welfare, as well as pulling other levers such as expanding and diversifying its workforce. On the economic front, while a slowing economy will necessitate more informed trade-offs, it does not point to a downfall scenario. Even with forecasts of lower growth China will still outpace most of the world, enabling China to evolve its economy. China’s debt is also manageable and does not appear to be holding China back from investing in technology and military capabilities. While transitioning to a consumer-led economic model is challenging; China’s abundance of consumers, a large internal market and high levels of savings offer further growth opportunities. Despite unsound comparisons with Japan, reform failures, and the risk of civil strife, China will continue its rise. This essay contends that China remains on the rising side of Kennedy’s theory and that domestic problems will not be its downfall.

References & Bibliography

- Black, J. S., & Morrison, A. J. (2019, September 1). Can china avoid a growth crisis? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/09/can-china-avoid-a-growth-crisis

- China: The rise of a trade titan. (2021, April 27). UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/news/china-rise-trade-titan

- China’s economy will not overtake the US until 2060, if ever. (2022, October 24). Financial Times.

- China’s road to pragmatism. (n.d.). Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://global.matthewsasia.com/insights/sinology/2022/chinas-road-to-pragmatism/

- Collins, A. S. E., Gabriel B. (n.d.). A dangerous decade of Chinese power is here. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/18/china-danger-military-missile-taiwan/

- Dudash, S. (n.d.). Chinese opportunity: Evergrande won’t be a Lehman moment. Forbes. Retrieved 29 December 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2021/10/01/chinese-opportunity-evergrande-wont-be-a-lehman-moment/

- Exclusive: Foreign insurers gear up to tap China’s $1.6 trillion pensions business – sources. (2019, April 12). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-pensions-exclusive-idUSKCN1RO0FA

- Fenby, J. (2009). The Penguin history of modern China: The fall and rise of a great power, 1850 – 2008. Penguin.

- Global pension statistics—OECD. (n.d.). Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/finance/private-pensions/globalpensionstatistics.htm

- Harding, C. (2019). Japan story: In search of a nation, 1850 to the present. Penguin Books.

- Has China reached the peak of its powers? (n.d.). The Economist. Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2022/11/18/has-china-reached-the-peak-of-its-powers?utm_medium=cpc.adword.pd&utm_source=google&ppccampaignID=18156330227&ppcadID=&utm_campaign=a.22brand_pmax&utm_content=conversion.direct-response.anonymous&gclid=CjwKCAiA76-dBhByEiwAA0_s9VCoCHS7pVMH4ZWkpDGbSBr3PnwL0W-JfEOxvuv6HudnQIkeNHgmsRoCGGAQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

- Hillman, J. (n.d.). China’s belt and road is full of holes. Center For Strategic & International Studies. Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-full-holes

- Hofman, B. (2021, June 6). China’s new population numbers won’t doom its growth. East Asia Forum. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/06/06/chinas-new-population-numbers-wont-doom-its-growth/

- Huang, Y. (2017). Cracking the China conundrum: Why conventional economic wisdom is wrong. Oxford University Press.

- Ignatius, A. (2021, May 1). “Americans don’t know how capitalist china is”. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/05/americans-dont-know-how-capitalist-china-is

- Ikenberry, J. G. (1996). The future of international leadership. Political Science Quarterly, 111(3), 389.

- India will soon overtake China to become the most populous country in the world. (n.d.). Our World in Data. Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://ourworldindata.org/india-will-soon-overtake-china-to-become-the-most-populous-country-in-the-world

- Iskyan, K. (n.d.). Why China won’t face a Japan-like “lost decade”. Retrieved 29 December 2022, from https://sg.finance.yahoo.com/news/why-china-won-t-face-025059764.html

- Jacques, M. (2012). When China rules the world: The end of the western world and the birth of a new global order (2. ed., [greatly expanded and fully updated]). Penguin Books.

- Kennedy, P. M. (1989). The rise and fall of the great powers: Economic change and military conflict from 1500 to 2000. Fontana Press.

- Kroeber, A. (2020). China’s economy what everyone needs to know (Second). Oxford University Press.

- Lousy demographics will not stop China’s rise. (2021, May 3). Financial Times.

- Luo, B. (2022, July 20). China will get rich before it grows old. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2015-04-20/china-will-get-rich-it-grows-old

- Magnus, G. (2018). Red flags: Why Xi’s China is in jeopardy. Yale University Press.

- Manufacturing by Country 2022. (n.d.). Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/manufacturing-by-country

- Mastro, S. O., & Scissors, D. (2022). China hasn’t reached the peak of its powers. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/china-hasnt-reached-peak-its-power

- Minzner, C. (2022, June 27). China’s doomed fight against demographic decline. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2022-05-03/chinas-doomed-fight-against-demographic-decline

- Osnos, E. (2022, October 23). Xi Jinping’s historic bid at the communist party congress. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/10/31/xi-jinpings-historic-bid-at-the-communist-party-congress

- Peng, X. (n.d.). China’s population is about to shrink for the first time since the great famine struck 60 years ago. Here’s what it means for the world. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 29 December 2022, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/07/china-population-shrink-60-years-world/

- Pettis, M. (2022). How china trapped itself—The ccp’s economic model has left it with only bad choices. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/how-china-trapped-itself

- Population, total—China | data. (n.d.). Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CN

- Rajah, R., & Leng, A. (2022). Revising down the rise of china. Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/revising-down-rise-china

- Rapidly ageing China rolls out private pension scheme in 36 cities. (2022, November 25). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/china-pension-private-pension-idUSKBN2SF0EY

- Rosen, D. (2022a, June 16). The age of slow growth in china. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2022-04-15/age-slow-growth-china

- Rosen, D. (2022b, December 3). China’s economic reckoning. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-06-22/chinas-economic-reckoning

- Rudd, K. (2022). The avoidable war: The dangers of a catastrophic conflict between the US and XI Jinping’s China. PublicAffairs.

- Rudyak, M., & Contributors, C. F. (n.d.). Does china’s economy keep xi awake at night? Foreign Policy. Retrieved 29 December 2022, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/10/13/does-chinas-economy-keep-xi-awake-at-night/

- Tepperman, J. (2022). China’s dangerous decline. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-dangerous-decline

- Westad, O. A. (2022, December 29). The sources of Chinese conduct. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-08-12/sources-chinese-conduct

- White, E. (2022, October 5). Xi Jinping’s last chance to revive the Chinese economy. Financial Times.

- Wight, M. (1978). Power politics (H. Bull & C. Holbraad, Eds.). Leicester University Press.

- Yan, X. (2014). From keeping a low profile to striving for achievement. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 7(2), 153–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pou027

- Zhang, L., Brooks, R., Ding, D., Ding, H., He, H., Lu, J., & Mano, R. (2018). China’s high savings: Drivers, prospects, and policies1. IMF Working Papers, 2018(277). https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484388778.001.A001

- Zipser, D., Hui, D., Zhou , J., & Zhang, C. (2022). 2023 McKinsey china consumer report—A time of resilience. McKinsey & Company.

- 单学英. (n.d.). Demographic change not always bad. Retrieved 28 December 2022, from https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202206/17/WS62abb610a310fd2b29e632cd.html

Leave a comment