Introduction

In his speech to the Russian public on 24th February 2022, Putin cited NATO enlargement as the primary reason for Russia’s ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine. In the speech, he claimed that Russia had spent three decades attempting to come to an accommodation with the alliance but to no avail. Moreover, he cited NATO enlargement and the increasingly assertive nature of the alliance as a direct threat to Russia. For Putin, the action in Ukraine was a reply to the broken promises supposedly made in the early 1990s “not to expand NATO eastward even by an inch”. His message to the Russian people was that NATO was “not only a very real threat to our interests but to the very existence of our state and its sovereignty”. Putin stated his belief that a Western-backed coup of neo-Nazis in Kyiv had the ultimate goal of retaking Crimea, with Russian enemies having “openly laid claim to several other Russian regions” (Putin, 2022, para, 14, 26 & 30). From his perspective, the ‘special operation’ was an inevitable action forced upon him by the West.

Some Western observers have framed Putin’s well-known hostility to NATO enlargement as evidence that the West ignored repeated Russian concerns and has created a crisis of their own making. At the forefront of the debate is the realist scholar John Mearsheimer, who famously rounded on Western policy in 2014, claiming the “taproot of the trouble is NATO enlargement” (Mearsheimer, 2014, p. 1). At the heart of his argument was the belief that the West had forgotten basic realist geopolitics and that NATO enlargement provoked Russia, resulting in the seizure of Crimea. This was an argument Mearsheimer put forward again in the summer of 2022, following the broader invasion, when he reiterated his view that the blame for the war lay with “America’s obsession with bringing Ukraine into NATO” (Mearsheimer, 2022, p. 13). Mearsheimer, however, was not alone, with Pillar, 2014; Roberts, 2017; and Walt, 2022, also making similar arguments. The view expressed by Mearsheimer and others provoked a backlash among commentators such as McFaul, 2014; Person 2014; Goldgeier, 2014; Motyl, 2015; Kostelka, 2022 and Rachman, 2023; citing Putin’s increasing authoritarianism and revisionist tendencies as better explanations for Russian actions against Ukraine.

Despite Russian rhetoric over NATO enlargement, this essay will argue that the role of enlargement as a cause of the war in Ukraine has been exaggerated and masks more critical factors. The first part of this essay will explore the case made by those promoting NATO enlargement as the cause. The second section will critique and recalibrate the significance of NATO enlargement in the ongoing debate. Finally, the third section will make the case that the war is better explained by Russia’s desire to destroy Ukrainian democracy and independence, consolidate dictatorship at home and return Russia to great power status.

Section 1: The NATO Enlargement Debate

Before arguing that other, more critical factors lie behind the war in Ukraine, it is essential to assess the role of NATO enlargement and recalibrate its importance within the debate. The discourse blaming NATO enlargement for events in Ukraine varies considerably, with Putin and the Kremlin relying heavily on historical perspectives. However, it is possible to define three core arguments:

- Previous commitments made to Russia not to enlarge the alliance eastward were broken, severely undermining the trust between Russia and NATO.

- Russia’s genuine security concerns were ignored, resulting in military action.

- NATO actions were provocative, exacerbating an already tense relationship, undermining attempts to assuage Russia of NATO intentions and increasing the likelihood of Russian military action.

Broken Promises

The first argument is that historic commitments made to Russia by Western powers not to enlarge NATO eastward at the end of the Cold War were broken. Commentary relating to apparent pledges not to enlarge NATO is widespread. As Wolff points out, “Russia firmly believes NATO offered a gentleman’s agreement in 1990” not to enlarge NATO and that Russia sees the West as having destroyed the possibility of Russia existing within a new European security architecture (Wolff, 2015, p. 1106). Pillar concurs, arguing that NATO enlargement went against commitments made to the Soviet Union, foregoing further enlargement in exchange for Soviet acceptance of German unity (Pillar, 2014). The notion of broken promises has also been highlighted by Russian Senator Alexei Pushkov, who points to the apparent commitment made by German Chancellor Helmut Kohl to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990 not to place military assets in former East Germany after accession to NATO – a promise he believes was broken soon after unification was completed (Pushkov, 1997). The suggestion that the US and its allies broke agreements on enlargement is regarded by many as a significant aggravating factor and a possible explanation for Russia’s aggressive stance towards NATO.

Disregarded Concerns

The second argument is that Russia’s genuine security concerns and repeated warnings against NATO enlargement were ignored, resulting in subsequent military action. While Putin’s national address on 22nd February 2022 appeared to many as conjecture, his mention of Russia’s three-decade mission to come to terms with NATO is correct. As Wolff points out, Russian reaction to NATO’s initial enlargement scoping exercise in the early 1990s was extremely adverse, a view which never recovered even during periods of apparent Russian-NATO detente such as the signing of the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997 (Wolff, 2015).

Many commentators refer to statements from Russian government officials over the years as evidence that clear and explicit warnings were ignored. For example, as Wolf points out, the Russian government made clear in 1999 that further enlargement “would cross a red line” (Wolff, 2015, p. 1108), while in 2006, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated that further expansion to include Georgia and Ukraine would cause a “colossal geopolitical shift” (Walsh, 2006, para. 3). Similarly, Russian foreign affairs expert Nadezhda Arbatova suggests Russian concerns were ignored especially in light of consistent anti-NATO remarks made by Putin in 2007 and Medvedev in 2010 (Arbatova, 2022). Even starker is the apparent remark by Putin to President Bush that Ukraine would cease to exist if it attempted to join NATO (Mearsheimer, 2014), a clear forewarning of the possibility of a pre-emptive armed intervention. Some have also pointed to the consistency of warnings, with Roberts arguing that “Putin has not changed his message since taking office in 2000. NATO – the West – has just failed to hear him” (Roberts, 2017, p. 49).

Several commentators point out the likely consequences of ignoring Russia’s concerns. For example, Pillar argues that in disregarding Russian concerns, it is hardly surprising that Russia, irritated by enlargement, would take action, as the US would if roles were reversed and a foreign power was attempting to subvert the Monroe Doctrine (Pillar, 2014, para. 6). Similarly, Carpenter argues that blame for the war in Ukraine must also be shared by NATO’s “tone-deaf policy toward Russia”, suggesting that in ignoring Russia’s enlargement concerns and failing to amend Western policy, conflict was inevitable (Carpenter, 2022, para. 1).

From these arguments emerges a narrative that the West ignored repeated Russian concerns and that some form of blowback, including conflict or area denial, was inevitable. For many commentators, the apparent denial of Russian agency, refusal to recognise Russian fears and the breaking of apparent commitments regarding enlargement is the root cause of Russian-NATO angst and the conflict in Ukraine.

A Provocative Alliance

The third argument is that NATO’s actions before, during and after enlargement has been provocative, exacerbating an increasingly tense relationship, undermining attempts to assuage Russia of NATO intentions and increasing the likelihood of Russian military action.

In highlighting such arguments, it is vital to explore NATO actions more broadly and beyond enlargement, especially given Putin’s desire to conflate enlargement and the alliance’s perceived assertiveness as a threat to Russia. Russian commentators have concurred with Putin’s criticism of NATO enlargement and its ‘out-of-area’ missions, with Arbatova arguing that NATO’s bombing of Serbia in 1999 was in direct contravention of the Russia-NATO Founding Act and partly responsible for the ongoing situation in Ukraine (Arbatova, 2022). Furthermore, while discounting the role and significance of enlargement in the debate, Marten argues that Russia feared the expansion of NATO’s role, especially in taking military action without UN authorisation (Marten, 2017). The argument that ‘out-of-area’ missions exacerbated tensions is also supported by Spassov, who posits that the US used NATO to gain geopolitical influence at Russia’s expense (Spassov, 2014).

Others argue that NATO undertook increasingly provocative actions as enlargement began. For example, Robert M Gates, the former US Secretary of Defence under President Obama, argues that the 2006 US decision to station troops in Romania and Bulgaria was an inflammatory move. Furthermore, he asserts that efforts to include Ukraine and Georgia in NATO were unnecessary and would inevitably lead to a negative Russian response (Gates, 2014). Similarly, Carpenter points to dramatic increases in NATO military drills and intercepts on the Russian frontier, NATO’s refusal to downgrade military exercises, and the establishment of a new base in Poland as policy decisions that aggravated tensions with Russia (Carpenter, 2020). The deepening relationship between NATO and Ukraine is also highlighted by Mearsheimer, who argues that Ukraine effectively became a “defacto member” in 2014 in light of the annual training of ten thousand Ukrainian troops under NATO auspices and its inclusion in NATO military and naval exercises (Mearsheimer, 2022, p. 20).

Those citing NATO as an explanation for the war have focused on NATO’s out-of-area missions, ill-judged deployments and its deepening relationship with Ukraine. For many critics, NATO’s ignoring of Russian concern was terrible enough, but aggravating the situation with provocative actions against mounting Russian anger was irresponsible and bound to lead to conflict.

Section 2: NATO enlargement isn’t the smoking gun

Whilst arguments blaming NATO enlargement for the war in Ukraine seem compelling, this essay contends that they are undermined on several grounds:

- The promises not to enlarge NATO, which Putin highlights as a betrayal, never occurred.

- Russia’s reaction to gradual NATO enlargement has been inconsistent and often indifferent.

- Russia’s lack of reaction to NATO deployments in the former Soviet states, together with NATO’s implementation of confidence-building measures and cautious deployments, discredits Russian rhetoric.

- Arguments blaming NATO’s ‘out-of-area’ missions do not stack up when considering Russia’s oscillation between acquiescence and support for NATO initiatives.

- The implausibility of Ukraine’s accession to NATO before the conflict rules out enlargement as a plausible explanation for Russian intervention in Ukraine.

Imagined Promises

Firstly, Putin’s claim of broken promises is inherently flawed. The West never made such a commitment to Russia. The Russian claims are based on back-and-forth preliminary conversations with Western officials prior to the official policy position announcement at the 1990 Washington Summit (Sarotte, 2014). Moreover, the very idea of enlargement negotiations is undermined by the fact that the talks in 1990 were primarily focused on the issue of East German NATO membership alone, with no debate over future eastward expansion, especially given the unresolved issue of the Warsaw Pact (Spohr, 2022). Given the tumultuous reality of the immediate post-Cold War period, it is reasonable to presume that NATO enlargement was a lower priority.

Detached Reactions

Secondly, looking again at the inconsistent and, at times, indifferent Russian response to NATO enlargement between 1994 and 2023 undermines the importance of NATO enlargement when appropriating blame for the war. The issue of NATO enlargement, even during the Yeltsin years, was not a significant obstacle, with Yeltsin toying with the idea of Russian membership and publically advising the US that the former Soviet states should look to join NATO as a collective group (Colton, 2008). This indifference was also seen in Putin, who showed no apparent agitation when the Baltic states joined NATO in 2004 (Pifer, 2022), provided it did not lead to the deployment of NATO installations (Marten, 2017) – something which NATO agreed to in its Russia-NATO Founding Act Treaty in 1997.

Even Putin’s public reaction to Ukrainian NATO membership is inconsistent. In 2002, in response to questions about Ukraine becoming a NATO member, Putin stated calmly, “At the end of the day, the decision is to be taken by NATO and Ukraine. It is a matter for those two partners” (Person & McFaul, 2022, p. 21). Moreover, Michael McFaul, the former US Ambassador to Russia, points out that both Putin and Medvedev never mentioned the issue of NATO enlargement in high-level conversations during the entirety of the Obama presidency (2009 – 2017) (McFaul, 2014). Fast forward to 2022, and news that Finland and Sweden are moving to join NATO has met only muted Russian reaction (Pifer, 2022) – a surprising response given Finland’s well-known military capability (Dorman, 2023) and Sweden’s renowned defence industry (Bowman et al., 2022).

Overall, Russian reaction to NATO enlargement has been inconsistent across three decades, with frequent episodes of silence or indifference. In light of Russia’s muted reaction, it is reasonable to question whether talk of NATO as an existential threat is little more than propaganda.

Rhetoric vs Reality

Thirdly, the case for blaming NATO enlargement is also undermined when comparing Russian rhetoric to operational responses on the ground. For example, despite Russia declaring NATO enlargement a menace in its military strategy documents (Kupchan, 2010), Marten points out that Russian combat forces along NATO-Russian borders decreased significantly between 2000 and 2014, undermining Russian rhetoric claiming NATO as an existential threat (Marten, 2017). Moreover, looking at the cautious nature of NATO deployments since enlargement also undermines Russian threat narratives. For example, in 2004, a small squadron of NATO military jets landed in Lithuania, only for Russia to acknowledge them as posing no risk to Russia (Gidadhubli, 2004). Moreover, while NATO did move military units into the Baltic states in response to Russia’s seizure of Crimea, they amounted to “no more than tripwire forces” (Pifer, 2022, p. 2). All this followed NATO’s efforts to assuage Russian fears by signing the Founding Act and implementing confidence-building measures, including prohibiting nuclear forces in any new NATO member.

NATO’s Helper

Fourthly, Putin’s criticism of NATO actions, particularly its ‘out of area’ missions, masks the stark reality that Russia has been heavily engaged with NATO operations and even supported some of its out-of-area missions, undermining Russian claims regarding the NATO threat. For example, after the 9/11 attacks in the US, Russia cooperated with NATO, allowing military equipment to be transported to Afghanistan across Russia (Gidadhubli, 2004). Furthermore, Putin helped coax the former Soviet Republics of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan into allowing the US to establish military bases for anti-terror missions (Person, McFaul, 2022), later Medvedev continued the arrangement with President Obama (McFaul, 2014), a set of counterintuitive actions given that military bases are inevitably long-term investments with evolving uses. Moreover, despite Russian anger at the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, in 2011, Russia abstained in the UN vote authorising the NATO bombing of Libya (Borger, 2011). These examples raise the inevitable question – why would Russia countenance engagement with an alliance it sees as so threatening? Given Russia’s cooperation and collaboration with NATO, it is reasonable to suggest that Russian protestations regarding the NATO threat require recalibration.

An Unlikely Membership

Finally, whilst Russia has pushed the argument that Ukraine joining NATO would cause a “colossal geopolitical shift” (Lavrov, 2006), support for Ukrainian membership and the implausibility of accession suggests this was not a realistic prospect, further undermining Russia’s pretext. While the declaration following the 2008 NATO Bucharest Summit outlined support for eventual Ukrainian membership, events quickly overtook it. President Obama sought a re-set in relations with President Medvedev and, in doing so, clearly stated that there would be no further enlargement to the east, including Ukraine and Georgia (Goldgeier, 2014). Likewise, France and Germany showed deep reticence and opposition to the prospect of Ukrainian NATO membership (Plokhy, 2018), effectively ruling it out, given the alliance’s policy of unanimous support for new members. Furthermore, the election of President Trump in 2016 saw direct relations with Putin improve whilst divisions within NATO grew, further pushing out the prospect and likelihood of Ukrainian membership in NATO.

Narratives blaming NATO enlargement fail to convince. In light of Russia’s inconsistent reaction to enlargement, its support for NATO actions and the implausibility of Ukrainian NATO membership, it is reasonable to suggest NATO enlargement is no smoking gun.

Section 3: Russia’s Casus Belli – Democracy, Dictatorship & Revisionism

While it is reasonable to suggest that NATO enlargement played a part in worsening relations between Russia and the West, it is overly prominent as an explanation for the war. This section will make the case that the war in Ukraine resulted from Putin’s desire to destroy Ukrainian democracy, consolidate dictatorship at home, and return Russia to the status of a great power.

Democracy Destruction

This essay posits that the war in Ukraine is Putin’s attempt to prevent an independent, democratic Ukraine that could inspire Russians to demand greater democracy, putting his regime at risk.

It is reasonable to suggest that Putin’s fear of democracy is lifelong and enduring. With Putin blaming Gorbachev’s ‘Perestroika’ for the collapse of the Soviet Union and the chaos of the 1990s (Service, 2020), it is no surprise that within his first year in office, he had taken control of Russia’s broadcast media and clamped down on dissent (Greene & Robertson, 2019). Over the next two decades, Russia became an ‘imitation democracy’ with election results falsified, opposition parties banned, and the constitution changed to favour Putin at the expense of the elected parliament (Furman, 2008).

As Horvath points out, the clampdown on democracy occurred whilst the economy was booming and the public was satiated (Horvath, 2011). Despite opinion poll results in his favour, Putin is aware of the fragility of support, with the president and his advisors constantly reviewing opinion polls (Greene & Robertson, 2019). Despite the impression of control, protests surfaced regularly over the next two decades. Protestors attacked welfare reforms (2005), election fraud (2011-12), regime corruption (2017), and pension reforms (2018). In his second presidential campaign in 2011, Putin was booed in front of a large stadium crowd (Service, 2020), while opposition leader Alexei Navalny caused a viral sensation in 2011 when he termed Putin’s United Russia a “party of crooks and thieves” in an anti-corruption campaign (Navalny, 2011).

The 2011 Bolotnaya protests against suspected electoral fraud lasted for months and involved up to two hundred thousand protesters (Greene & Robertson, 2019). The protests also evolved, focusing more on political rights and taking on a more Western, democratic and liberal feel (Robertson, 2013), no doubt causing unease in the Kremlin. Exacerbating Putin’s fears were events outside Russia in the former Soviet Republics and Serbia. The revolutions in Serbia (2000), Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004) and Kyrgyzstan (2005) sparked a dramatic change in how Russia viewed the democratic threat, with the Kremlin fearing a Russian-style’ velvet revolution’, compounded by the sight of orange (read Ukraine) protest decorations on the streets of Moscow, in support of democracy activities in Kyiv (Horvath, 2011). As Horvath points out, the Russian regime responded by creating regime-friendly youth organisations such as Nashi and placing draconian restrictions on foreign NGOs (Horvath, 2011).

For Putin, a Ukrainian democracy with an independent foreign policy is unacceptable. Putin’s goal in Ukraine is to stop democracy and bring Ukraine back under Russian control (Person & McFaul, 2022). For Putin and the Kremlin, Ukraine presents a dangerous inspiration and one relatable to the average Russian citizen. As Stoner suggests, Ukraine in 2014 represented a smaller version of Russia, one where its citizens might see in Maidan a blueprint for their own protests (Stoner, 2021). Similarly, Russian Mikhail Shishkin argues that Russia is doing everything to keep Ukraine out of Europe’s embrace and that “the Kremlin will never allow a democratic Russian-speaking state to exist”, implying it may embolden Russians seeking democracy who can see in Ukraine a re-imagined Russia. (Shishkin, 2023, p. 101). The intervention in Ukraine aims to prevent democratic protests in Ukraine from being repeated on the streets of Moscow or St Petersberg, as they nearly did during the election protests in 2011 (Person & McFaul, 2022). Similarly, Stoner suggests that for the Kremlin, the 2014 revolution against Yanukovych “could not be perceived as successful to Russians watching back home” (Stoner, 2021, p. 257).

The threat to Putin’s regime posed by Ukrainian democracy represents a much graver threat than the issue of NATO enlargement, as the Kremlin knows. Shishkin suggests it is not NATO enlargement that is the problem for Russia but Ukraine’s move westward towards democracy (Shishkin, 2023). Similarly, Stoner argues that protests pose a severe risk to the Kremlin’s authority and that “the Russian ‘street’ is thus far more threatening to Putin’s paternalist autocracy than NATO or the EU” (Stoner, 2021, p. 249). Finally, Person and McFaul point out that Putin’s complaints about NATO became more intense during bouts of democratic gain and reached a crescendo after military intervention in Ukraine, suggesting that NATO masks the real goal of the regime: the denial of democracy (Person & McFaul, 2022).

For Putin, a democratic Ukraine with a healthy civil society, fair elections and the ability to chart its own course on foreign policy is anathema. It would undermine the basis for his regime, intensify calls for democracy and inevitably raise questions about Russia’s future leadership transition due in 2024. For Putin, NATO enlargement is a useful pretext to obscure the real target: Ukrainian independence and democracy.

Consolidating Dictatorship

While Ukraine has proved a thorn in the side of the Kremlin, it has also allowed it to consolidate dictatorship at home. In the face of a slowing economy, intensifying domestic protests and a potential democratic transition in Ukraine, Putin has exploited Ukraine to strengthen autocracy and regime security.

Since the February 2022 invasion, Putin and the Kremlin have intensified efforts to consolidate power and eviscerate the opposition. The police and FSB have arrested 20,467 protestors, while the state has made references to ‘war’ and criticism of the army illegal (Kolesnikov, 2023). In addition, over 700,000 citizens have left the Russian Federation (Forbes Russia, 2022), with Kolesnikov putting the numbers fleeing to Kazakhstan alone at 2.9 million (Kolesnikov, 2023), no doubt, to avoid mobilisation, but much to the benefit of the Kremlin, which has lost a vast swathe of Russia’s more liberal-leaning population.

As Ostrovsky points out, events in Ukraine since 2014 have proved “both a threat and an opportunity”, with the Kremlin using the conflict as a justification to clamp down on the last remaining vestiges of non-Kremlin controlled media (Ostrovsky, 2018, p. 313). Similarly, Borenstein argues, the war in Ukraine has been “invaluable to domestic politics”, given the Kremlin’s desire to link the Maidan protests in Ukraine to the Russian opposition and to foster the link between chaos in Ukraine and the potential for its spread to Russia in the form of civil war (Borenstein, 2019, p. 227). For the Kremlin, Ukraine’s televised chaos and disruption is a useful warning to Russians about the possible ramifications of challenging the status quo.

Additionally, the Russo-Ukraine relations specialist Taras Kuzio suggests, “Russia’s dictatorship cannot exist without internal and external enemies” (Kuzio, 2022, p. 48), which reflects the efforts made by Putin and the Kremlin to link foreign brokers with attempts to ferment protest in Russia while also supporting the apparent neo-Nazi regime in Ukraine (Kuzio, 2022). As Ilya Yablokov outlines in her book ‘Fortress Russia’, the Kremlin has adopted conspiracy theories to bolster support for autocracy, disparage opponents and justify foreign policy efforts. As an example, she highlights the conspiracy actively promoted by the Kremlin that the US Ambassador to Russia, Michael McFaul, was working ardently to support a Russian-style’ colour revolution’, a plotline helped by his apparent desire to meet with a variety of domestic opposition groups (Yablokov, 2018). Such conspiracy theories tie back to Putin’s rhetoric that the West is out to destroy and dismember Russia with a Western plot to support a series of ‘colour revolutions’ ending in Russia itself (Putin, 2022). It also handily merges with the widespread belief among the Russian public that Putin rescued Russia from the chaos of the 1990s (Galeotti, 2022), fostering the idea that it is better to stick with Putin and overlook tightening autocracy than allow the chaos of democracy to return to the streets of Russia.

For Putin, Ukraine is useful in keeping the Russian population fearful, and the opposition cowed. The Kremlin has used the ongoing strife in Ukraine to display what could happen to Russia if its enemies are not dealt with in Ukraine and at home.

Revisionist Russia

A more important explanation for the war lies in Putin’s desire to return Russia to the status of a ‘great power,’ a notion popular with the Russian public that helps secure domestic cohesion, enhances regime security and corrects Russia’s perceived displacement as a great power following the Cold War.

In the annual State of the Nation address to the Russian parliament in 2005, Putin described the disintegration of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century”, one that left millions of Russians outside the Federation’s borders and the country plagued by separatist violence (Putin, 2005, para. 6). It was a narrative he returned to when announcing the annexation of Crimea in 2014 (Putin, 2014). For Putin, Russia had been robbed of its greatness. In his view, the West had attempted to “isolate and marginalise his country and deny it global status” (Galeotti, 2022, p. 178). Furthermore, Putin has been irritated by suggestions that Russia was no longer a great power and was especially irked by President Obama’s categorisation of Russia as a ‘regional power’ in March 2014 (Obama, 2014). In response, Putin has gone out of his way to speak up on global issues, strut Russia’s energy dominance and flex its military muscle (Easter, 2008). The seizure of Crimea and action against Ukraine is an attempt by Putin to return Russia to great power status.

As Person and McFaul argue, Putin perceives Russia as a great power controlling its own sphere of influence, where it reserves the authority to interfere and intervene in neighbouring states, such as Ukraine, as it sees fit (Person & McFaul, 2022). Putin is leveraging a widespread sentiment among Russian international relations experts who assert that “former Soviet states are not entitled to absolute sovereignty or foreign policy choice” (Cooley, 2019, p. 612). For Putin, Yanokovych’s fall in 2014 led to the halt of the proposed integration of Russia and Ukraine into a wider Eurasian Union – a cornerstone of Putin’s desire to both strengthen Russia’s sphere of influence and thwart Ukrainian attempts to sign a similar deal with the EU. As Plokhy points out, Putin’s attempt to change the Ukrainian position with massive loans and trade restrictions failed, with Russia then invading Crimea to provoke federalisation to influence opinion in Kyiv and restrict Ukraine’s manoeuvrability (Plokhy, 2017). For Putin, attempts at influencing Ukraine had not worked – now it was time to ‘force’ change.

For Putin, a more assertive foreign policy feeds into the expectations of the Russian public and strengthens domestic cohesion. As Ostrovsky points out, a survey in 2000 found that 55 percent of Russians anticipated Putin restoring Russia to great power status (Ostrovsky, 2018). Furthermore, Nadskakula-Kaczmarczuk argues that Putin’s desire to offer an alternative to the West is popular with the Russian public. She highlights a survey by the Levada Center, where over 80 percent of respondents believed it better for Russia to pursue a non-Western, uniquely Russian political model. Moreover, she points out that in research conducted in 2018, most respondents agreed that Russian prosperity was only possible through “controlling the zones of influence” (Nadskakula-Kaczmarczuk, 2017, p. 341). For Putin, the public was increasingly receptive to narratives of power and resurgence, something he could exploit with his plans for Ukraine.

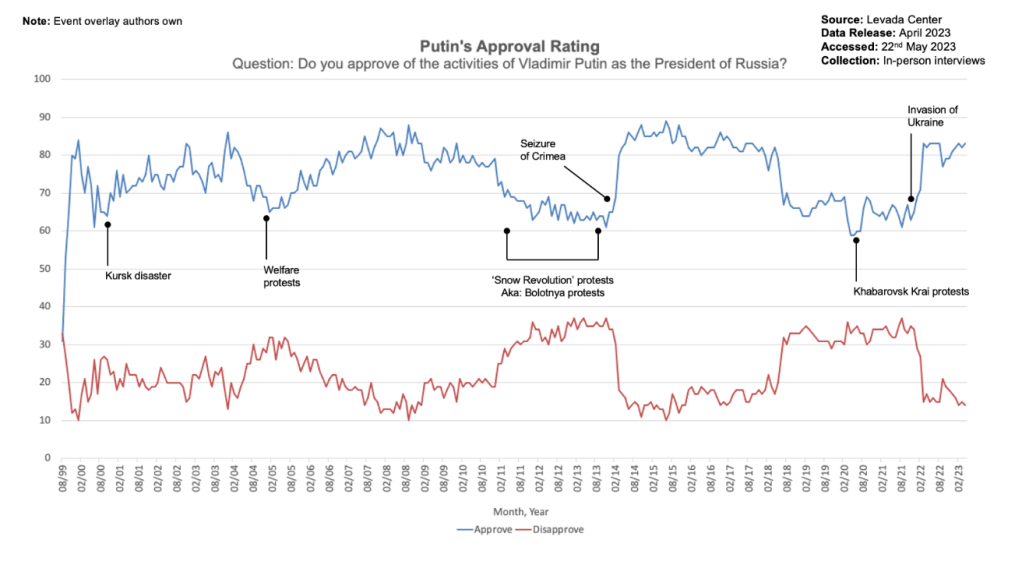

Putin’s willingness to undertake decisive foreign policy is rewarded in opinion polls, further suggesting that action in Ukraine had ulterior motives. As Service suggests, Putin is benefitting from the convention that foreign policy is the one area that unites Russians across the political spectrum (Service, 2020). For example, as a result of Putin’s invasion of Crimea, his approval rating increased from 60% to 80%, with Ostrovsky suggesting that the bulk of the middle class who had protested back in 2011 had moved back into his column (Ostrovsky, 2018). Moreover, as Service points out, international criticism of Putin has only increased his popularity with the Russian public, who are content to have a leader willing to stand up and defend Russia on the world stage. Similarly, Nadskakula-Kaczmarczuk points out that Levada surveys conducted in 2014 saw the vast majority of respondents agreeing that “Putin acted like a hero in defending the country against enemies” (Nadskakula-Kaczmarczuk, 2017, p. 341). Putin is using Ukraine to exploit a nexus between his desire for Russian great power status and the public appetite for it.

Putin’s determination to return Russia to great power dovetails with his seizure of Crimea and continued aggression in Ukraine. As Allison points out, the seizure of Crimea fits with Russian ambitions to project global power beyond the Russian Federation, especially in light of Russian military plans for expanding military and navy bases beyond Russia (Allison, 2014). Even Putin himself gave the game away when in June 2022, he compared his endeavour in Ukraine to that undertaken by Peter the Great in the seventeenth century during this lengthy war against Sweden, stating, “Apparently, it is also our lot to return [what is Russia’s] and strengthen [the country]” (Putin, 2022). In Putin’s eyes, he was the latest Russian leader embroiled in a conflict looking to ensure Russia’s status as a great power.

Putin’s desire to return Russia to its historic status as a ‘great power’ is a better explanation for the war in Ukraine. The popularity of decisive intervention, competition with the West, and its perceived benefit for social cohesion suggest that Russian power dynamics are a more critical rationale for the war in Ukraine.

Conclusion

This essay did not set out to dismiss NATO enlargement as a factor behind the war in Ukraine but instead to recalibrate it against other more critical factors. While it is reasonable to argue that NATO and the West have certainly made mistakes with NATO enlargement, it is farfetched to assign it as the primary reason for the current situation in Ukraine, as Putin did in his national address following the broader invasion in 2022.

As this essay has argued, Russia has been inconsistent in its opposition to NATO. Early desires to join the alliance, collaboration in the transportation of assets across Russian territory and mixed messages on ‘out of area’ missions undermine the Russian narrative of the NATO threat. The response to NATO enlargement clearly shows the difference between discourse and reality, with rhetoric about NATO corresponding with falling Russian troop numbers bordering NATO states. On reflection, it is clear to observers that NATO is no smoking gun but is a useful prop used by Putin and the Kremlin as a pretext for a war in Ukraine to quash its democratic experiment and the risk such a democracy poses to the autocratic Russian state. The fact that anger at NATO coincides with democratic gains suggests it is a proxy for the genuine source of Russian anxiety and anger.

As an explanation for the war, NATO enlargement is overshadowed by Putin’s desire to destroy Ukrainian democracy and independence, consolidate dictatorship at home and return Russia to great power status.

Putin undertook the war from a position of weakness. The fragile nature of his hold on power necessitated action to prevent Ukraine’s evolution to European-style democracy that risked providing Russian citizens with a blueprint for a democratic transition. The war in Ukraine has also been used to consolidate dictatorship at home, enabling the arrests of protestors, the handing out of lengthy jail sentences, the fleeing of liberals and the closure of the last remaining independent media outlets that threaten Putin’s regime. It has provided the Kremlin with a unifying narrative that secures domestic cohesion and maintains regime security.

Furthermore, the war was Putin’s attempt at returning Russia to the status of a great power and, in doing so, delivering on the Russian public’s expectations and strengthening autocratic control. For Putin, the war was an attempt to secure Russia’s sphere of influence and reserve its right to intervene in its neighbouring states as it sees fit. Finally, it was a reply to those in the West that Russia remains a global player of immense importance and one that will be at the top table whatever it takes.

Despite repeated rhetoric from the Kremlin, the muted reactions to Finland and soon Sweden’s accession to NATO suggest the prominence enlargement has been given in the debate requires recalibration. To deny any role of NATO enlargement in explaining the war in Ukraine would be inaccurate, but other, more salient factors are better explanations for the war. In recalibrating, NATO enlargement remains a possible factor, but one that ranks below Putin’s desire to destroy Ukrainian democracy, consolidate dictatorship at home and return Russia to great power status.

Bibliography:

- Allison, R. (2014). Russian ‘deniable’ intervention in Ukraine: How and why Russia broke the rules. International Affairs, 90(6), 1255–1297. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12170

- Borenstein, E. (2019). Plots against Russia: Conspiracy and fantasy after socialism. Cornell University Press.

- Borger, J. (2011, March). Libya no-fly resolution reveals global split in UN. Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/mar/18/libya-no-fly-resolution-split

- Bowman, B., Brobst, R., Sullivan, J., & Hardie, J. (2022, July). [Defense Industry News]. Finland and Sweden in NATO Are Strategic Assets, Not Liabilities. https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2022/07/20/finland-and-sweden-in-nato-are-strategic-assets-not-liabilities/

- Carpenter, T. G. (2022a, February). CATO Institute [Think Tank]. Many Predicted NATO Expansion Would Lead to War. Those Warnings Were Ignored. https://www.cato.org/commentary/many-predicted-nato-expansion-would-lead-war-those-warnings-were-ignored

- Carpenter, T. G. (2022b, February). [Think Tank Cato Institute]. Ignored Warnings: How NATO Expansion Led to the Current Ukraine Tragedy. https://www.cato.org/commentary/ignored-warnings-how-nato-expansion-led-current-ukraine-tragedy

- Colton, T. J. (2008). Yeltsin: A life. Basic Books.

- Cooley, A. (2019). Ordering Eurasia: The rise and decline of liberal internationalism in the post-communist space. Security Studies, 28(3), 588–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2019.1604988

- Dorman, A. (2023, April). [Think Tank Chatham House]. Finland Brings Great Value to NATO’s Future Deterrence. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/04/finland-brings-great-value-natos-future-deterrence

- Easter, G. M. (2008). The Russian state in the time of Putin. Post-Soviet Affairs, 24(3), 199–230. https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.24.3.199

- GALEOTTI, M. (2022). A short history of Russia. EBURY PRESS.

- Gidadhubli, R. G. (2004). Expansion of NATO: Russia’s Dilemma. Economic and Political Weekly, 39(19), 1885–1887.

- Goldgeier, J. (2014, April). Stop Blaming NATO for Putin’s Provocations. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/117423/nato-not-blame-putins-actions

- Greene, S. A., & Robertson, G. B. (2019). Putin v. the people: The perilous politics of a divided Russia. Yale University Press.

- Horvath, R. (2011). Putin’s ‘preventive counter-revolution’: Post-soviet authoritarianism and the spectre of velvet revolution. Europe-Asia Studies, 63(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2011.534299

- Kennan, G. F. (1997, February). A Fateful Error. New York Times, 23.

- Kolesnikov, A. (2023). How Russians Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the War. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/how-russians-learned-stop-worrying-and-love-war

- Kostelka, F. (2022, July). [Corporate blog of the European University Institute]. John Mearsheimer’s Lecture on Ukraine: Why He Is Wrong and What Are the Consequences? https://euideas.eui.eu/2022/07/11/john-mearsheimers-lecture-on-ukraine-why-he-is-wrong-and-what-are-the-consequences/

- Kupchan, C. A. (2010). NATO’s Final Frontier: Why Russia Should Join the Atlantic Alliance. Foreign Affairs, 89(3), 100–112.

- Kuzio, T. (2022). Why Russia Invaded Ukraine. Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, 21, 40–51.

- Marten, K. (2017). The Growth of NATO-Russia Tensions (Reducing Tensions Between Russia and NATO). Council on Foreign Relations.

- Marten, K. (2018). Reconsidering NATO expansion: A counterfactual analysis of Russia and the West in the 1990s. European Journal of International Security, 3(2), 135–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2017.16

- McFaul, M., Sestanovich, S., & Mearsheimer, J. (2014). Faulty Powers—Who Started the Ukraine Crisis? Foreign Affairs, 93(6), 167–178.

- Mearscheimer, J. (2014). Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault. Foreign Affairs, 93(5), 77–84.

- Mearscheimer, J. (2022). The Causes and Consequences of the Ukraine War. Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, 21, 12–27.

- Motyl, A. J. (2015). The Surrealism of Realism: Misreading the War in Ukraine. World Affairs, 177(5), 75–84.

- Nadezhda, A. (2022, April). Was NATO Enlargement a Mistake? [Ask the Experts Panel]. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ask-the-experts/2022-04-19/was-nato-enlargement-mistake

- Nadskakuła-Kaczmarczyk, O. (2017). Sources of the legitimacy of Vladimir Putin’s power in today’s Russia. Politeja, 14(4(49)), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.12797/Politeja.14.2017.49.17

- NATO Bucharest Summit Declaration 2008. (2008). NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_8443.htm

- Obama: Russia a regional power. (2014, March). CNN. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PkQUzeZbLEs

- Ostrovsky, A. (2015). The Invention of Russia: From Gorbachev’s Freedom to Putin’s War. Viking.

- Person, R., & McFaul, M. (2022). What Putin fears most. Journal of Democracy, 33(2), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2022.0015

- Pifer, S. (n.d.). [Think Tank]. One. More. Time. It’s Not about NATO. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/one-more-time-its-not-about-nato/

- Pillar, P. R. (2014, April). The National Interest [Journal]. NATO Expansion and the Road to Simferopol. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/paul-pillar/nato-expansion-the-road-simferopol-10200

- Plokhi, S. M. (2017). Lost Kingdom: A history of Russian nationalism from Ivan the Great to Vladimir Putin. Penguin Books.

- Pushkov, A. (1997). Don’t Isolate Us: A Russian View of NATO Expansion. The National Interest, 47, 58–63.

- Putin, V. (2005). Annual Address to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation. Kremlin. http://www.en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/22931

- Putin, V. (2014). Address by President of the Russian Federation. Kremlin. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603

- Rachman, G. (2023, February). It makes no sense to blame the West for the Ukraine war. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/2d65c763-c36f-4507-8a7d-13517032aa22

- Roberts, K. (2017). Understanding Putin: The politics of identity and geopolitics in Russian foreign policy discourse. International Journal: Canada’s Journal of Global Policy Analysis, 72(1), 28–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020702017692609

- Robertson, G. (2013). Protesting Putinism: The election protests of 2011-2012 in broader perspective. Problems of Post-Communism, 60(2), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.2753/PPC1075-8216600202

- Russia calls NATO plans ‘colossal’ shift. (2006, June). New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/07/world/europe/07iht-kiev.1915928.html

- Sarotte, M. E. (2014). A Broken Promise? What the West Really Told Moscow About NATO Expansion. Foreign Affairs, September / October 2014.

- Service, R. (2020). The Penguin History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the twenty-first century (Fifth edition published with revisions). Penguin Books.

- Shishkin, M. (2023). My Russia: War or peace? (G. Ipsen, Trans.). Riverrun.

- Spassov, P. (2014). Nato, Russia and European security: Lessons learned from conflicts in Kosovo and Libya. Connections: The Quarterly Journal, 13(3), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.13.3.02

- Spohr, K. (2022, March). Exposing the myth of Western betrayal of Russia over NATO’s eastern enlargement [University]. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/exposing-the-myth-of-western-betrayal-of-Russia/

- Stoner, K. (2021). Russia resurrected: Its power and purpose in a new global order. Oxford University Press.

- Walt, S. M. (2022, January). Liberal Illusions Caused the Ukraine Crisis. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/19/ukraine-russia-nato-crisis-liberal-illusions/

- Wolff, A. T. (2015). The future of NATO enlargement after the Ukraine crisis. International Affairs, 91(5), 1103–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12400

- Yablokov, I. (2018). Fortress Russia: Conspiracy theories in post-Soviet Russia. Polity.

Leave a comment